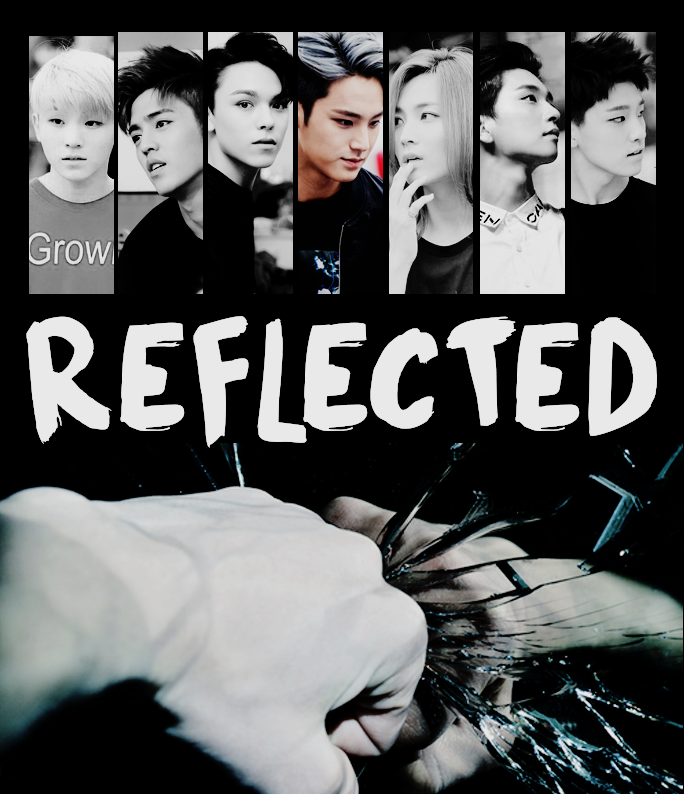

Reflected

Reflected

Jihoon liked to say that Mingyu was made of rock music and teen angst.

“And cigarette smoke,” Vernon would always chime in, usually from his favorite spot in the kitchen, and Mingyu’s cheeks would turn pink. (It was actually kind of ridiculous how ashamed Mingyu was of his smoking, especially he had very little shame he felt in any other aspect of his life. He went to such great lengths to hide his smoking from his friends and his father, and neither could possibly care less. He never traveled without gum in his pocket, always kept body spray in his bag and never let anyone see him smoke. Nobody cared but him. So why, then, did he always get so embarrassed when someone brought it up?)

In Mingyu’s mind, by Jihoon’s same logic, they were all made of something.

“Yeah,” Joshua would say, poindexter that he was. “Oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, calcium and phosphorous. Are you dumb, or did you sleep through biology last year?”

Josh, as an example, was made of scientific facts, miscellaneous statistics and pent-up rage. He had a mind like a steel trap, his memory damn near superhuman. If he read it in a textbook or heard it from a teacher, it was in his brain forever. Exams that made other kids cry with frustration and feelings of failure? Josh aced without a second thought, and he seemed to write complicated research papers with the same ease a toddler scribbled in a coloring book. He was so smart, in fact, that it occasionally bordered on worrisome. What else was Joshua Hong capable of? Just how deep did that wealth of intelligence truly run?

The only scholastic subcategory where he he fell short was class participation. He didn’t answer questions or contribute to class discussions, sure that his matter-of-fact attitude would read as condescending and, subsequently, threatening to the Neanderthals in his class, and he already had enough trouble with them. If keeping his hand and head down when his teacher asked an easy question about Francis Bacon would mean the difference between getting to his next class on time and getting shoved face-first into a trash can again, it was an easy choice to make.

By all accounts, Josh was probably big and strong enough to fight back. But he never had. Not even once. He’d been pantsed, shoved into lockers, thrown into dumpsters and just generally beaten into submission by guys with half his IQ. Joshua was tall enough and broad enough to generate a decent amount of strength, so why not turn it around on his tormentors? Why spend your life being brutalized at the hands of alphas? Why was he so content to be a hapless beta forever?

It was something Mingyu didn’t understand and it also something that usually turned Josh into an . Joshua’s anger at the rest of the world (the lunkheads that tortured him, the girls that wouldn’t date him, the teachers who let him get his kicked, the classmates that just looked the other way, thankful it wasn’t them) sometimes turned him inside-out and forced him to lash out at the group. It happened like clockwork every couple of months. He screamed at Vernon for smoking so much, picked on Jeonghan for the way he looked, pushed Jihoon around just because he was bigger than him. There was this look he’d get in his eyes when he snapped, this cold, unrelenting fury that everyone in their group understood. He was dangerous like that, all the raw power of a hurricane with no end in sight, and they tried to steer clear until he got it out of his system.

They’d let him blow his stack, watch as he threw things out windows and punched walls, all the while screaming himself hoarse, shouting empty threats and violent vulgarities at anyone who would listen. And then, when the storm passed, Joshua deflated, returning to his usual glory as the quietest member of their group.

If things got especially dicey, Seungcheol was really good at talking him down. He was the oldest member of their merry group of misfits and he tended to act like something of a rodeo clown. Josh would get that look in his eyes, his face tight, his jaw clenched, his fingers twitching themselves into fists, and Seungcheol knew how to get in the way and soften the blow.

That was just Seungcheol’s way.

Personally, Mingyu found Joshua’s complex unpredictability to be annoying. All that brooding and pouting when the solution to his problems were so simple? He didn’t get it. But, hey, in the grand scheme of things, who was Mingyu of all people to judge how another guy blew off steam?

Besides, being friends with Joshua came with perks. His parents were very, very wealthy and very, very busy, a winning combination for a high school senior with degenerate friends. His father owned a contracting company and his mother was a real-estate mogul. And what did that mean for Josh and his pals? Well, it meant they always had a place to go. Josh was a master sleuth, an expert at knowing when to be silent during dinnertime discussions and when to ask his folks seemingly innocuous questions. Simply put, he knew where to find empty houses. Vacant vacation homes, places under construction, new and furnished houses that hadn’t quite hit the market yet. His friends craved privacy and freedom, and Joshua knew just where they could get it.

In the grand scheme of things, his violent outbursts were a small price to pay considering he was the one who’d found them a home base.

According to Josh, the two-story Georgian Colonial was halfway between wasteland and paradise. Apparently, it was in real estate limbo, having been left to a pair of dueling siblings by a sick aunt. Though they’d mostly picked the place clean, they couldn’t agree on what to do with the house itself. The brother wanted to sell it while the sister wanted to preserve it, leaving it as-is for the next generation of snot-nosed brats that might want it. According to Josh’s mother, it seemed like the sister was simply dragging her feet out of spite. She was so spiteful, in fact, that she continued to pay the utilities just to piss off her brother.

As it stood, that two-story Georgian Colonial sat in the middle of town, completely unused and Josh decided to take one for the team. Literally. His mother had been the agent that the feuding brother had contacted about selling the house. As such, she had the key on file. Once he figured out where it was, it was just a matter of making seven copies and getting the original back before his mother noticed it was gone.

For a guy as smart as Josh, it was a cakewalk.

He handed out the keys like he was giving candy to trick-or-treaters, then hit them with house rules.

No smoking. (That rule was the first broken, as well as the most frequently broken.)

No fighting inside the house. (If you had a problem, you took it outside. Wild West rules. No dueling in the saloon.)

No bringing girls (or boys, in the case of Jeonghan) back to the house.

No breaking windows, denting walls or otherwise damaging the home.

And, most importantly, no outsiders. This was their place. Seven keys for seven guys, and that was it. It was their sanctuary, their refuge, their headquarters. It wasn’t a place to throw ragers, nor was it some sort of bachelor-pad-slash--den.

It was their hideout, and God only knew how many things each of them had to hide from.

It was ironic, of course, that the boy with the least amount of danger at home had been the one to procure their safehouse, but sometimes life was like that. When a golden opportunity presented itself, it was best not to pull at the thread that held it together. The other six didn’t question it. They just accepted their keys and offered their thanks.

It wasn’t long before virtually every house rule had been broken. Some sins were more forgivable than others (telling Vernon not to smoke was like telling a dog not to back or a bird not to fly) and others were met with much more scrutiny. But when it became clear that the epic clash of the greedy siblings had fizzled into an incredibly apathetic stalemate, when they were sure that their little slice of heaven wasn’t in danger of being pulled out from under them, they made themselves comfortable.

Aunt Helen (they actually never learned the name of the old broad whose house it had been, and Seungcheol was the one who started inexplicably referring to her as their late Aunt Helen) had simple tastes. Once her niece and nephew had gone through and claimed anything of value, the boys were left with little to work with – three old mattresses, a plastic-covered couch, a faded loveseat, obsolete kitchen appliances, a TV from the mid-seventies and one working bathroom.

Fortunately, they didn’t require very much. Most of all, they needed a place to crash when got too real. Seungcheol was the only one who didn’t live with his parents, and his landlord didn’t want teenagers hanging around the apartment complex. (At least that was what Seungcheol told them. Mingyu had a creeping suspicion that it had a lot more to do with Seungcheol not wanting them at his place. He didn’t exactly live in the nicest part of town and Dino didn’t need any more temptation.)

In time, they’d all sort of taken over a corner of the house, claiming their individual spots like cats in an alley. Jeonghan took the upstairs bedroom, the one that used to belong to Aunt Helen, because he was the only one not skeeved out by sleeping in a dead woman’s bed.

“We don’t know she died here,” Jeonghan said. He was going through Aunt Helen’s closet, trying on whatever suited his fancy. At the moment, he was donning a dated feather boa and costume earrings. “She could’ve died anywhere. Besides, I like the room. It has… ambiance.”

What it had was an awful lot of creepy porcelain dolls and the unmoving, almost living stench of rose perfume. But Jeonghan wasn’t bothered by it. In fact, he barely changed a thing once he got rid of the dolls. (He’d told Vernon that their eerie, unblinking eyes creeped out some of his boyfriends and then made Vernon promise not to mention that he’d been bringing guys back to the house.) Aunt Helen’s bedroom was almost exactly how she’d left it, just with more men’s clothing in dirty piles on the floor and more condoms in the nightstand. (Presumably.)

Jihoon took the other upstairs bedroom. There wasn’t much rhyme or reason for it beyond the fact that it boasted a twin bed and he was the smallest member of the group. The room itself was non-descript, nearly bare. White walls, white curtains, an empty dresser and lots of dust. Jihoon didn’t like to bring tons personal effects into the house, something about bad juju, but he did replace the sheets.

“Who still uses wool blankets?” he’d asked, shoving the damn thing into the bottom drawer of the dresser. He itched at his arms, the skin red and puffy, an allergy he hadn’t known about. “Was Helen a pilgrim or something?”

“That’s Aunt Helen to you,” Seungcheol had said. He’d been making Jihoon’s bed for him. “Don’t disrespect her in her own home.”

All Jihoon had contributed to his home-away-from home was a few comic books, his journal, a pack of drawing pens and his own pillow. (Something about the idea of not knowing whose head was on that pillow before his gave him the creeps. It was one of the reasons he didn’t like hotels.)

Joshua took the downstairs bedroom. His door was the only in the house with a working lock and he made use of it. He insisted on his privacy, something the others didn’t really question. (Mingyu found it odd, but Mingyu found a lot of things about Joshua to be odd. He was an only child living in a mansion with distant parents. Didn’t he have all the privacy he needed?) Mingyu had never actually been in Joshua’s room but he could make some educated guesses regarding the aesthetics. Based on everything else he knew about his friend, he was picturing sunlight-blocking curtains, a state-of-the-art stereo, a top-of-the-line computer atop a thousand-dollar desk and maybe a white noise machine. They’d all sort of made a silent pact not to bring too much in or throw too much out but since Joshua had gotten them the house in the first place, the same unspoken rules didn’t apply to him.

Vernon didn’t sleep over all that often and when he did, he usually just took whatever spot was available. It wasn’t often that the whole group spent the night at Aunt Helen’s so there was usually a bed or couch cushion up for grabs. If push came to shove, he’d be fine to sleep on the floor with a spare pillow. The only thing he really cared about was the gazebo out back. Sitting under the stars, smoking a joint and listening to 70s music on his old school iPod was pretty much his idea of paradise, and he usually ended up biking home at the end of the night and sleeping in his own bed.

Mingyu, meanwhile, slept on the couch. It wasn’t a pull-out couch and it wasn’t particularly comfortable but the protective plastic had kept the upholstery clean and soft. Given that he was the biggest guy in the group, a three-cushion sofa wasn’t the most perfect fit, but for him, it was Xanadu. He’d never been an insomniac, someone fast to fall asleep and a sound sleeper after the fact, so what did he care? He treated the little coffee table like a nightstand, using it to hold his phone, charger, wallet and Gatorade. (He hid his cigarettes under the couch and kept his lighter in his pocket as he slept.)

Dino usually crashed on the loveseat, which sort of made him Mingyu’s roommate, but sleeping in the same room didn’t make Mingyu understand the kid any more. (And was it really considered sleeping in the same room if Dino was usually completely passed out and barely breathing?) Tiny as he was, even Jihoon couldn’t sleep comfortably on the small loveseat, but Dino didn’t seem to mind. Mingyu could only imagine the pain he’d feel if he spent a night curled up on that lounge, all the stiffness in his neck and joints, but he figured all the Vicodin Dino took probably helped ease the post-loveseat soreness.

Mingyu didn’t have anything against Dino. He actually kind of liked him. There was something charming about the kid. Next to Joshua, he was likely the smartest guy in the group but while Joshua was all book smarts and fun facts, Dino was streetwise. He was resourceful, quick, innovative. There were very few problems he was unable to solve one way or another, and life had yet to throw Dino anything he couldn’t handle.

But that wasn’t for lack of trying. At just sixteen-years-old, he been given a whole hell of a lot to handle, but who among them hadn’t? They’d all been put through the ringer in some way or another (though Mingyu regretfully considered Joshua and Vernon to have gotten a much better hand than the rest of them) so why was Dino the only one who needed copious amounts of drugs to deal with it?

“Vernon needs drugs to cope,” Jihoon had once pointed out when Mingyu brought it up. They were downtown the year before, taking in the annual food truck festival. They were perhaps the two most different members of the group, everything from height to skin tone to social status. Mingyu was tall, dark and handsome, a jock who played on the baseball team and gave weaker kids wedgies because he didn’t know how to handle with the way his dad treated him. Jihoon was petite, pale, a sensitive, intelligent geek who liked to read and draw. But at their cores, they were the most similar. They tended to hang out the most outside of the group and when they did, they tended to talk about their friends. It was from a place of concern, though, not malice or jealousy. It was simply easier to discuss the group’s problem when most of the group was someplace else.

“He smokes a lot of weed,” Mingyu shrugged, taking a sloppy bite out of a chicken taco. “But that’s a far cry from what Dino does. He’s only a sophomore and he’s high all the time. On the hard stuff, Jihoon. Vicodin, Adderall, Xanax. Shouldn’t we, like, do something?”

Jihoon snorted.

“Sure,” he said. “Then, right after that, we’ll have an intervention for Jeonghan’s addiction.” He rolled his eyes and shook his head, his bangs moving with the breeze. “Come on. Let’s go see if we can find a decent dessert truck.”

He let the topic drop for a few months, then brought it up to Seungcheol.

Seungcheol was the uncontested leader of their group, the oldest and the wisest. He’d battled alcoholism in his teens and come out the other side something of a standup guy. He’d been living on his own since he was seventeen, working two (sometimes three) jobs to make ends meet. Now, at twenty-two, he didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t get in trouble with the law. He kept an eye on the rest of the guys, made sure that they ate, that they slept, that the went to school, that they didn’t OD or bleed to death.

He and Seungcheol had gotten burgers after Seungcheol got off work, and they ate them outside the restaurant and watched cars drive by.

“Don’t worry about him,” Seungcheol had said. “The kid has his demons but we all do. He’s paying his dues. I was wild in my teen years, too, and look at me now. Sometimes you can’t bounce back until you hit rock bottom. He’s still in school and he’s not a thug. You know how hard he works to help keep food on the table at his house. Everyone needs an escape.”

“He’s sixteen,” Mingyu said, aware that his birthday a month before only dictated him Dino’s senior by two years. “He should escape by playing videogames or something.”

Seungcheol smirked and put a big hand on Mingyu’s shoulder.

“The kid’s a hustler,” he said. “He’ll be okay. Better he work through his now and sort himself out before college. Things only get worse as you age. Trust me. It’s better this way.”

Mingyu wanted to point out that Dino’s parents could barely afford electricity, let alone college, but he bit his tongue and reached for another fry. Sometimes he felt like he and his friends were all wearing glasses and all saw things through different lenses. What was perfectly clear to Jihoon and Seungcheol didn’t make a of sense to him and Vernon, and what made sense to Dino and Jeonghan was absurd to Joshua.

They were seven very different boys. He figured the same could be said for any group of friends but he thought that his circle operated at extremes. At times, it didn’t even feel like they were all the same species.

They could be an obnoxious bunch of motherers but Mingyu knew how they all seven of them got to be exactly the way the way that they were. It wasn’t by accident or by chance, though some could argue it was by fate. It was nature and nurture, or too much of the former and not quite enough of the latter. They were direct products of their environments, for better or for worse, and when it came down to it, all they really had to count on was each other.

Whether or not that was a good thing was still up for debate.

Take Jeonghan, as an example. He was, perhaps, the member of the group Mingyu knew least. The same rules applied to Jeonghan that applied to everyone else in their group – if anyone ever laid a hand on him, Mingyu would rip them to shreds with his bare hands – but they weren’t super close. They had no common interests, no overlap. Their personalities clashed. Mingyu tended to be hyper-masculine, inflating his ego to protect the insecurities that lay beneath. It was something he inherited from his father and something he hated about himself, but it was something that made him look sideways at Jeonghan, a guy about his age that routinely slept with men and kept himself looking prettier than any boy ought to.

Jeonghan kept his long hair perfectly groomed, and was known to wear eyeliner and polish his nails. Maybe it was his confidence that bothered Mingyu, the way that Jeonghan could walk the halls in a women’s jacket and high heeled shoes and have more honest-to-goodness self-esteem than he could, or maybe it was just his teenage homophobia coming to a head and prickling in his underdeveloped brain. In the grand scheme of things, though, he didn’t hate Jeonghan. Jeonghan was a good person. He was loyal, charming, funny. More than once, when Mingyu forgot his wallet or just didn’t have enough cash to get by, Jeonghan bought him lunch, or gave him half of whatever he’d brought for himself. When Mingyu was close to getting kicked off the baseball team, Jeonghan tutored him in history and expected nothing in return.

But Jeonghan also slept around. He was just a year younger than Mingyu but had developed a real reputation for having with older guys. Not a year or two older, not a case of an underclassman sleeping with college guys. He ed with older guys, adults, middle-aged guy with wives and kids and jobs in finance. As far as Mingyu knew, Jeonghan didn’t date, didn’t associate with guys his own age. There were other gay guys at school, even a few in their grade, but Jeonghan wasn’t interested.

Mingyu walked in on them once, Jeonghan and a forty-year-old rolling around in Aunt Helen’s bed. It was back when he was still new to the group. Jeonghan was barely sixteen. Because he had nowhere else to go that night, Mingyu simply sat downstairs and watched football videos on his phone. Seungcheol showed up after work, the way he always did on Thursdays, and asked Mingyu whose car was in the driveway.

“Jeonghan is upstairs ing some guy,” Mingyu blurted out. “Not, like, a teenager but a guy. A man. I knew he was gay but… that guy could be his father. Why is he doing that? He brags about having with guys but I always thought that he meant kids our age. Does he always mean adults?”

His questions were met with silence. Seungcheol nodded slowly, the only sign at all that he was listening to what Mingyu was saying. He rubbed his jaw, took a deep breath and then sat beside Mingyu on the couch, nodding his chin at Mingyu’s phone. Knowingly, Mingyu shut it off and slipped it into the pocket of his hoodie.

“You know about Jeonghan’s home life?”

“He’s a foster kid,” Mingyu said, one of the few things he knew about Jeonghan. They’d had a class together when Mingyu was in tenth grade. The topic of adoption had come up in a debate and Jeonghan had mentioned something about it.

Seungcheol nodded again.

“But do you know why he’s a foster kid?” He didn’t. Why would he? He’d only known Jeonghan a few months. Seungcheol in a breath and said, “Jeonghan was abused as a kid. A lot, actually. By his mother’s boyfriend, and then some guys in foster care.”

“Like me?” Mingyu asked, piping up with a pathetic sort of hopefulness. His tone was regretful, shameful but for a split second, he thought that he had someone to relate to, that he had a new friend who would understand him.

“No,” Seungcheol said. “Not like you.” He smiled sadly. “These guys… touched him. him, Mingyu. It happened for a few years. And this…” He gestured up to the ceiling, meaning to point to Aunt Helen’s room. “This is just how he deals with it.”

“How do you know all this?” Mingyu asked, his throat suddenly dry.

“People trust me,” Seungcheol said with a lopsided grin. “They tell me things. Same way I know about your dad.” Mingyu shrank under Seungcheol’s gaze, hyper-aware of the way his friend’s eyes suddenly fell to the bruise on his jaw. “I know it seems ed up but don’t think too much about it, okay? He’s sixteen. That makes him legal. Don’t feel like you’re doing anything wrong or that you’re complicit somehow, okay? This is just Jeonghan’s baggage. Don’t worry about it.”

Mingyu bit the inside of his cheek and nodded, processing his words. Then he asked, “Is that why Jeonghan’s gay? Because of what happened to him?”

All in one motion, Seungcheol scoffed, rolled his eyes and punched Mingyu in the thigh.

“Don’t be stupid,” he said. “Of course not.” Mingyu looked offended for a minute, suddenly self-conscious about his own ignorance, and rubbed the sore spot on his thigh. Seungcheol was stronger than he looked. Seeing this, Seungcheol sighed and put his hand on Mingyu’s shoulder. It was the first time he’d done that, but it would become a pretty regular gesture between them. “You hungry? I think we’ve got some food in the fridge. I was thinking breakfast for dinner. You like potatoes and eggs?”

So that was Jeonghan, then. For whatever reason, learning more about Jeonghan made Mingyu respect him more. They still weren’t compatible, guys that wouldn’t be friends in any other universe, but Jeonghan was just a kid doing his best, just like the rest of them. But Mingyu really didn’t like the idea of his friend being passed around by men the same age as their parents and teachers. He didn’t know him that well at the time but the thought of Jeonghan being used like that made his skin crawl.

But it was Jeonghan’s cross to bear.

They all had their burdens.

They all had different reasons for staying at Aunt Helen’s. For Jeonghan, it was because he couldn’t bear to be around his foster parents. Whether they were abusing him, too, or if he just plain didn’t like them, Mingyu didn’t know. But Mingyu could relate. Mingyu hid out at Helen’s because he didn’t want to be near his father.

Joshua went because he was lonely, or at least that was Mingyu’s take on it. He had no friends, no girlfriend, no one to talk to at home. His parents were too busy making money to pay much attention to their kid, and his aggressive personality was likely to scare off any classmates stupid enough to try and get close to him. Without Helen’s house and the rest of the guys, what did Joshua have except a big, fat bank account?

Vernon hung out because Vernon didn’t have anything better to do. At nineteen-years-old, he was the second oldest of the group, and he was set to repeat his senior year for a third time. He was a pizza delivery boy, a classic under-achieving stoner with wealthy parents who had given up on him.

Jihoon had once expressed how sad he felt for Vernon, something that Mingyu couldn’t understand.

“You feel bad for a rich kid who smokes a lot of dope?” Mingyu asked. “Why?”

“His parents don’t give a about him,” Jihoon said.

“Why do you say that? They haven’t kicked his , haven’t kicked him out, haven’t done anything to him.”

“Exactly,” said Jihoon. “They don’t care. You have to care about someone to kick their and kick them out.” (Mingyu disagreed there.) “If they gave a , they’d cut him off, throw his out, make him work harder. But they’ve given up. They don’t care. They’re just going to let him waste away to nothing. Dude, he’s still going to be in remedial math when he’s twenty-five. It’s sad. He’s never going to be anything.”

Mingyu preferred not to look at it that way. Vernon was a nice enough guy. He laughed a lot, giggled, like a little kid, and always seemed to be smiling. But Mingyu couldn’t say much about him other than the fact that he smoked more in a week than most kids did in a year. It seemed like Vernon only hung out with them because no other group wanted him. (But really… wasn’t that true for all seven of them?)

Jihoon went to Aunt Helen’s because he craved the freedom to be himself. Being himself at school meant eating lunch in dumpster and being himself at home meant ridicule from the rest of his conservative family. He wasn’t big enough or manly enough for his father and older brothers. Comic books and sci-fi novels and animated films weren’t for men and any time he showed any real interest in something, they set out to destroy it.

At least at Helen’s, he could draw in peace.

Besides, he genuinely liked the other guys. He considered them to be friends. What was better than hiding out with your friends?

Mingyu wasn’t sure why Dino hung around. He was something of a wild card, a kid who always seemed to be talking too fast and doing too many things at once. It was no secret that he was high most of the time, always hopped up on something and buzzing around the house like a strung-out hummingbird, but Mingyu never truly understood his role in the group. He was the baby, sure, and, arguably, the most ed up, but what purpose did he serve? What spot did he fill?

Mingyu knew that Dino’s family was poor. His parents were working-class, doing their best, and he had two younger sisters. Not many reputable employers were looking to hire a doped up sixteen-year-old and so Dino couldn’t make money the old-fashioned way. But he loved his family and he wanted to help so, in true Dino fashion, he got creative.

He wasn’t willing to sell himself (he was no Jeonghan, after all) but he was willing to sell other things. It wasn’t uncommon to find him digging around in the trash, collecting bottles or looking for valuables under the pier. If he could get his hands on it, he’d try and sell it. Smooth-talker that he was, he usually succeeded.

But Dino’s priorities were split, fifty-fifty. He cared deeply for his family and wanted nothing more than to help provide for them. He loved his sisters endlessly and would go to the ends of the earth to make sure they had enough to eat and clothes to keep them warm. But he also had a nasty drug habit that demanded his attention.

As it were, all of the money he received from any of his various “odd-jobs” was divvied up between his family and his habit. Half the money went to his family’s fridge and the other half went up his nose.

It was an incredibly delicate balance, especially for a sixteen-year-old boy, and it kind of made Mingyu’s problems seem paler in comparison. Sure, his father smacked him around but at least he wasn’t hopelessly addicted to anything yet. Their group seemed to operate on a sliding scale of . Was it wrong that he was comforted by the fact that he didn’t have it the worst? Or was that sort of selfishness simply a side-effect of adolescence?

Mingyu’s life had been pretty great until he turned ten. On his third day of fifth grade, his mother was killed in a car crash. He hadn’t known it was even possible to feel grief like that, didn’t know that humans were capable of such pain. But things only got worse from there. He thought he’d been dropped to the depths of hell the day they buried his mother, but his suffering was just getting started.

Beyond just being an angel that kept hot meals on the table and monsters out of his closet, Mingyu’s mother was, it turned out, was the thing keeping his father together. His father was inherently distant, a blue-collar guy with simple tastes and a bad temper. He was the type to get irrationally angry over minor inconveniences but Mom was always there to guide him gently back to a calmer path. He was wound too tight, overworked and underpaid with an ego too big for the few skills he had. But Mingyu’s mother loved him anyway, and that love was the thing that had always kept him hinged.

With her gone, he was free to be himself, a small, cruel man who put in sixty-hour work weeks at jobs that didn’t matter, working for people who didn’t respect him. He came home angry, fists curled, back sore. He drank his dinner, inhaling six-pack after six-pack of cheap beer, and planted his in his ratty old recliner, eyes glued to TV until he inevitably passed out from exhaustion and inebriation.

Some nights, he didn’t fall asleep and some nights, shouting at ESPN and Fox News wasn’t enough to quell his rage. His anger was chronic, tangible, a terminal disease that rotted him from the inside out. He’d once been a man that stood tall and now he hunched, his body creaking like an old, wooden floor. His hatred for the world, the world without his wife, took its toll. It was like a wildfire, raging inside of him and everything Mingyu did seemed to only fan the flames.

As a kid, he’d kept track of the reasons he got hit. In his juvenile mind, if he could figure out the rules to the game, he stood a chance of winning. His father was grieving and he was taking his grief out on Mingyu. Okay, fine. Mingyu could deal with that. He’d just have to be on his best behavior. He left his baseball cleats in the doorway and his father tripped, and that earned Mingyu an open-hand slap across the face. He’d tried to make his own dinner and started (but then extinguished) a small fire, and the smoke alarm woke his father from his nap. That had gotten his arm twisted behind his back.

He mapped it out in his brain. He needed to listen. He needed to speak softly. He needed to be respectful. He cleaned up after himself, he did his homework, he took out the trash without being asked. He was the perfect son.

But he still got hit.

He got hit for breathing too loud, for showering too early in the morning, for asking about the grocery list, for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. He got hit because his father wanted to hit him.

Mingyu quickly grew out of trying to be the perfect son and instead just tried to survive. He timed his comings-and-goings so that he could spend as little time around his father as possible. When they were forced to be in the same room together, he spoke only when spoken to and kept his head down. He was curt but polite and made sure to avoid all of his father’s hot-button issues.

Was it a perfect system? No. He still managed to earn himself dozens of black eyes three broken bones. But by the time Mingyu was thirteen or fourteen, things had sort of plateaued. He and his father had reached something of an apathetic coexistence. Dad worked two jobs to keep the lights on, leaving Mingyu home alone to fend for himself. Other young teens might’ve used the opportunity to woo girls or start drinking recreationally but Mingyu wasn’t willing to risk it.

One beer can, one wrapper, one whiff of foreign perfume and his father would’ve dislocated every bone in his body.

Mingyu spent as much time as possible at friend’s houses, pretending their well-adjusted, well-intentioned parents were his own and that there were two adults somewhere that loved him. And when he was alone, he tried to relish in it. He exercised (lots of push-ups and sit-ups while he fantasized about the day he’d be big enough to fight back) and went to the batting range and spent lonely nights walking the backstreets of his neighborhood.

At least when he was alone, nobody was hitting him.

By high school, Mingyu had become a bully.

He wasn’t proud of it and in reality, it didn’t bring him the relief he thought it would. His father would come home drunk and call him a worthless piece of , and Mingyu would go to school the next day and wail on an innocent classmate who’d done nothing but look at him wrong. Dad would throw him over the coffee table for forgetting to start the dishwasher and Mingyu would spend the next day going on a rampage, shoving kids into walls and towel-whipping weaker guys in the locker room.

It didn’t make him feel any better, but once he’d been branded a bully, it was kind of hard to break the habit. He was who he was.

(It was ironic now that he was friends with Jihoon and Joshua, two kids who seemed to have been born with targets on their backs, but Mingyu would eviscerate anyone who dared to mess with them when he was around. What happened when they were apart, however, was their business. They needed to stand up for themselves someday. They needed to learn how to stand on their own two feet.)

Mingyu was turning sixteen when he met Seungcheol. He’d been smoking outside a local convenience store, eye swollen shut from a recent, unexpected beating, when an older, smaller man approached him.

“You should quit,” he said. “Those things will kill you.”

“I know you?” Mingyu asked, already sizing him up. He was fresh off an -kicking and just dying to work out some unresolved rage. Unless this guy was trained in jiu jitsu, Mingyu could definitely take him.

“You know Joshua?” Seungcheol shot back. His confidence was… abundantly clear. His hands were in the pockets of his jeans, his chin up, his shoulders back. He could’ve been the owner of 7-Eleven for all the assurance he carried in his body language.

“Hong?” Mingyu raised an eyebrow. At that point, he and Joshua were acquaintances at best. They had two classes together and had been partnered up once for a history project. Joshua was sort of an oddball but Mingyu admired his dry sense of humor. “I know him. Why?”

“What about Jihoon?”

“Jihoon Lee?” Mingyu asked, blowing smoke in the other direction. With his free hand, he gestured near his chest. “About ye high? He’s my friend. Again, why?”

Jihoon and Mingyu had met by chance. Jihoon was a grade younger than him but he’d found Mingyu in the back of the library once, icing a bruise, and given him tips on how to avoid getting taken down by a bully. Mingyu smirked, wanting to tell this little guy that he was the bully, not the one getting bullied (at least not in the traditional sense) but Jihoon had been so genuine in his delivery that he didn’t feel it appropriate. He just thanked him and asked if there were any bullies Jihoon needed taking care of.

A weird friendship had been born that day.

The fact that this guy, this arrogant, square-jawed guy, knew both Jihoon and Josh was… unlikely. It was an uncomfortable coincidence that didn’t lend itself to a grungy alley that smelled like piss and blue raspberry Slurpee.

“They’re friends of mine,” he said. “We’ve kind of got a group of guys that hang out. Jihoon mentioned that you might be interested.”

Uneasy, Mingyu blew a smoke ring.

“Why would he say that?”

The guy pointed to his Mingyu’s eye.

“Where’d you get the shiner?”

Mingyu squinted with his good eye.

“What’s it to you?”

“A guy needs like-minded friends,” he went on, unbothered by Mingyu’s indifference. “Guys like us need to stick together.”

“I literally have no idea what you’re talking about,” Mingyu spat, throwing the remainder of his cigarette to the ground and stomping it with the toe of his Converse.

“Jihoon vouched for you,” he continued. “He said you’re a good guy with somewhat of a rough home life and that’s sort of our thing. I like to help out guys like you, guys like Jihoon.”

“Are you a narc or something? A social worker?”

The guy laughed and it made him seem five years younger.

“I’m just a guy who’s been through some ,” he said. “I see younger guys struggling and I want to help. No one was there to help me. I guess I’m trying to be the person I needed when I was younger. And I trust Jihoon’s judgment. He says you’re a good guy that needs a little help.” He opened his arms, smirking smugly. “So he sent me.”

Mingyu was a complicated mix of concerned, off-put and confused, but didn’t make any move to walk away or brush him off.

Then the man offered his hand.

“I’m Seungcheol,” he said. “Let me buy you a soda or something and I’ll tell you a little about myself. If you still think I’m a narc, you can tell me to off. You can even keep the soda.”

Mingyu grinned. There was something about this guy, something that felt strangely… significant.

He wasn’t sure why but he felt something in that moment, something important, something worth remembering. So he did. Every detail, from the smoke on his tongue to the color of Seungcheol’s sneakers. It was a unity born in a dirty sort of serendipity, but it was significant to Mingyu all the same.

Then he reached out and shook his hand.

“Alright,” he said. “Whatever.”

They went inside the 7-Eleven, Mingyu bought him a Coke and Slim Jim, and the rest was history. He was introduced to Vernon and Jeonghan a few days later, and they all met Dino six months after that.

Back-alley destiny was really a force to be reckoned with.

Two years had passed. They had Aunt Helen’s state, and each other. What else was there?

They all had their crosses to bear, the demons from which they needed to escape.

Joshua had his anger, his disassociation, his lack of community ties.

Jihoon had his loneliness, his depression, his fleeting sense of self.

Jeonghan had his baggage, his ual transgressions, all the half- older men on his phone.

Vernon had his underachieving nature, his dependency on dope and his otherwise empty personality.

Dino had poverty, trouble with the law and a rampant drug addiction.

Seungcheol had nothing but love to give, an insatiable need to help people.

And Mingyu? He had a drunk for a father, a scurrilous man who didn’t know or care if his only son was dead or alive. He had a bad habit of picking on weaker kids to fruitlessly try and recover the shattered pieces of his self-esteem, and a dozen empty packs of cigarettes stuffed under his mattress.

They were imperfect. Mingyu thought he saw pieces of himself reflected in the other guys and pieces of them in him. He shared Jihoon’s yearning and Josh’s rage and Seungcheol’s sense of loyalty. They were the same, but different, and the reflections of each personality and each story made up the shining mirror that was their group.

Of course there were struggles. These were the teen years, after all, and they were supposed to be messy. Regardless of the darkness, there was an innocence there, a naivety, and blanketed in the warmth of ignorant adolescence, Mingyu felt safe. He knew firsthand how cruel the world could be, saw it himself and saw it on the faces of his friends, but he also knew joy. He knew fun. He knew humor and solidarity and brotherhood. One day, he hoped to know freedom.

Still, he thought it was a minor miracle that he managed to graduate high school. Joshua graduated with him, though he had a much higher GPA than Mingyu. The other boys came to the ceremony, even if Mingyu’s dad claimed he had to work that afternoon and just couldn’t get his shift covered, and Josh’s family took everyone out for an expensive dinner afterwards to celebrate.

The boys decided to memorialize the occasion on their own about a month later. Mingyu and Josh had graduated their own way, so why not celebrate their own way, too?

To be fair, Mingyu didn’t normally do drugs. He’d smoked with Vernon once or twice but didn’t care for it and the that Dino was into scared him. But when Seungcheol produced a small bag of white powder from his backpack and proudly declared it a graduation present, Mingyu had a hard time saying no. It was Seungcheol, after all. He’d never do anything that would hurt any of them, never put any of them in danger.

Besides, the drugs hadn’t been Seungcheol’s only present.

Joshua, Jihoon and Vernon were already with Seungcheol when Mingyu showed up late to Aunt Helen’s. Vernon, probably the first to arrive, was already stoned off his gourd and babbling about the origins of the universe. There was food on the table, fried chicken and fixings from the fast food place where Seungcheol sometimes picked up shifts, and Mingyu dug in, not bothering to explain why he was late.

He took his usual spot on the couch that also served as his bed and watched whatever grainy 90s sitcom was playing on Aunt Helen’s fossil of a television set. Though greasy, the food hit the spot and refilled his energy, and the company of his friends, however apathetic they seemed, did a lot to quell the sore spots in his soul.

A moment later, Seungcheol pulled something from his backpack.

“Here,” said Seungcheol, tossing a small, wrapped box at Mingyu. Even with a full plate of food in his hands, Mingyu snatched it from the air with the grace of a polished athlete.

“What’s this?”

“Most people call it a gift,” Seungcheol deadpanned. “It’s a token of my affection, you see, with the purpose of celebrating and commemorating a special occasion. Open it, you dope.”

Mingyu did as he was told and seconds later, he found himself both embarrassed and touched. It was a Zippo lighter, one of the good, refillable ones with the shiny silver exterior. Seungcheol had gotten it engraved with Mingyu’s initials and a message – Congrats on graduating but please quit smoking.

He laughed out loud, his cheeks taking on an unfamiliar shade of pink as he slid the lighter into the pocket of his jeans.

“Thanks, man,” he said, trying not to look as flustered as he felt. “I love it.”

“You’ve earned it,” Seungcheol said, slapping his arm. “You’ve come a long way.”

Mingyu really wanted to believe him, wanted to believe, perhaps naively, that his hardships had built up his character and made him someone greater than who he’d been.

It had been a rough year.

Mingyu had graduated by the skin of his teeth, the exact opposite of Josh who had graduated third in their class. He’d had somewhat of a disappointing baseball season and a real bone to pick with Mr. Simmons, his English teacher that seemed to be hellbent on making his life worse than it already did.

And then there was Yoona.

He wasn’t sure enough had gone on between them for her to be considered his first love. He was pretty sure he’d loved her but what did that even mean? They’d met at a party the summer before senior year and he was smitten the second she said hello. She was smart, and pretty, the type of all-American high school girl that all the teen movies said would end up with a guy just like him – athletic, arrogant, kind of stupid and not quite good enough for her.

They’d gone on a few dates, spent a few more house parties all tangled up together on the couch and on the dance floor, stayed up late texting each other when they should have been sleeping or studying. He’d even gotten to second base once after a baseball game where he’d hit the walk-off homer and been everyone’s hero.

But their small town was becoming a cesspool. There were lots of groups like his, lots of ed up teenagers with nowhere to go and nothing better to do but get into trouble. The only real difference between Mingyu’s friends and the local thugs was that those other gangs didn’t have Seungcheol to keep them on the straight and narrow. With a severe shortage of mentors and reliable father figures in town, crime rates were up, and it didn’t take long for that sort of deviance to find its way into Mingyu’s life.

More specifically, though, it found Yoona.

There was a modern-day bandit on the loose, a lone-wolf type, some real low-down piece of who was responsible for a string of recent robberies. It had started at the beginning of June and quickly grew into a pandemic. He’d been targeting high school kids, stealing cell phones and tablets and computers and wallets, all while wearing a creepy plastic clown mask he’d probably picked up at the party store for a buck.

Mingyu had heard about it, both through the grape vine and on the local news, but thought nothing of it. Beyond the fact that he was poor and had absolutely nothing of value worth stealing, Mingyu was bigger and stronger than this prick. Though nobody saw his face through the mask, all of the victim’s reported their attacker to be about 5’7.

Mingyu sort of half-hoped that the bastard would try to sneak up on him. He’d pound the son of a into the pavement and be hailed a hero by the whole town. Hell, the police might even give him a reward. (And he could really use the money. Now that he was eighteen and out of school, his father was demanding he pay rent. The number he likely pulled out of his was astronomical and Mingyu was having trouble scraping it all together. Why couldn’t he have been better at baseball? His dad liked to remind him over and over and over again that he was a failure, a weak athlete who never had any shot at college ball, let alone the pros. That’s why Mingyu had been slinging hash at a local diner, though he’d been keeping that detail to himself, and that’s why he’d been late to the graduation party. He was taking whatever shifts were available, desperate to get the money together before the end of July.)

Three weeks before graduation, he’d had plans with Yoona and two of her girlfriends. They were supposed to meet at 6:45 but his new boss, a sadistic, uppity prick with a superiority complex, made him work an extra hour just for s and giggles. His phone had died in the middle of his shift, meaning that he couldn’t call Yoona and tell her he’d be late. In the end, he didn’t show up until 8:15, not even bothering to change out of his work clothes because he didn’t want to be any later.

But it was too late. The cops were already there.

The bandit had struck again and this time, he’d brought along two friends. Maybe he’d decided that being a lone wolf just wasn’t quite as advantageous as working in a team. Whatever it was, he’d come with backup and it had paid off. After liberating the girls of their money, jewelry and devices, the guys got greedy. Apparently, it hadn’t escalated to but that was purely by chance. Forcible touching, the police had called it, and then a good Samaritan had come upon the scene and the guys got scared off.

Mingyu had been over an hour late to his date and someone had d and mugged his girlfriend. Almost-girlfriend. Would-have-been-girlfriend. Now-ex-girlfriend. When he’d shown up, she was wrapped in a shock blanket, crying, and talking to police about her mother’s pearls that she’d likely never see again. She saw him but she couldn’t look at him.

After that, she’d stopped calling, stopped meeting him for lunch, stopped walking with him to class. She didn’t look at him in the hallway, didn’t answer his texts, didn’t acknowledge that he even existed. He understood completely and didn’t blame her for any of it. He was supposed to be with her that night and he wasn’t. He was supposed to protect her and he didn’t and she hated him for it.

He hated him, too.

Yoona was going to a good college while Mingyu would stay in town and amount to exactly nothing. Of course their relationship, whatever it was, had come with a time-limit. He’d been playing with house money since the day that he met her. But this wasn’t how he wanted it to end.

He spent the three days after that binge drinking at Aunt Helen’s, puking his guts out and making empty threats at the other guys because that was how Kim men mourned the women they loved.

No tears, no feelings, just destruction. He was his father’s son.

So when Seungcheol arranged the powder from the bag in four neat lines on the coffee table that usually served as his nightstand, Mingyu didn’t even bother asking what it was. It was a gift, and a way to celebrate the end of a ty year, and Mingyu could accept it at face value.

Jihoon could not.

“?” he asked, looking up from his comic book. He’d been on the love seat, sitting quietly. Mingyu knew he was jealous of him and Joshua, knew that Jihoon hated high school and wanted out sooner rather than later.

Seungcheol shook his head.

“You think I’m made of money?” he smirked. Jihoon didn’t smirk back. “No. It’s ketamine. It’s like but it won’t ruin your life after one hit. The perfect celebration drug, young man.”

“I thought you’re Mr. Clean and Sober,” Joshua said. He was sitting on the floor, playing on his phone. Aunt Helen’s house didn’t have wifi but Josh could afford the best data plan Verizon had to offer.

“I won’t be partaking,” Seungcheol said nobly. “This is a gift for my friends. I’ll be here, as always, to make sure nobody dies.” He tipped an imaginary hat and bowed graciously. “What would you do without me?”

“Probably just take some weed from Vernon,” Joshua said without looking up from his phone.

“So you don’t want any, then?”

“I didn’t say that,” Joshua said smugly. He locked his phone, slid it in his pocket and moved himself towards the coffee table, bowing his head and snorting an entire line of ketamine without missing a beat. Mingyu wasn’t sure whether or not to be impressed. Joshua fell back onto the floor, grinning, and wiped his nose with the back of his hand.

“Thanks, captain,” he said, giving Seungcheol a mock salute. “Nothing like getting high and watching The Golden Girls.”

“Making Aunt Helen proud,” Vernon chortled from where he sat at the kitchen table. He laughed at his own joke, then looked to Jihoon. “If you don’t want to try K, you can have a joint, Jihoon. No peer pressure in this circle.”

Jihoon looked to Seungcheol as though looking for permission and Seungcheol just smiled.

“Party how you want, kid,” he said. “No judgment.” Jihoon seemed placated by that and nodded in Vernon’s direction. Vernon ran a hand through his hair, wavy and unruly, and smiled back, his usual, carefree beam. Mingyu wondered if Vernon ever frowned, then watched as he clamored out from behind the kitchen table, hopped over the back of the loveseat and landed beside Jihoon, offering him what was left of his blunt. He wrapped his arm affectionately or perhaps protectively around Jihoon’s shoulders and nodded at Seungcheol.

“Where’d you get this anyway?”

“I have my sources,” he said. “Why? You want some?”

Vernon shook his head.

“Not my style,” he said, ruffling his hair again. He put his hand on his chest, presenting himself proudly. “I’m an organic man.”

From the floor, Joshua snorted with laughter.

“Can you imagine Vern on something stronger than suburban weed?” he asked. It sounded rhetorical. He threw his head back and laughed some more, and when he looked back to the group, he was wearing a familiar expression – the sleepy, dazed face he sported when he made fun of Vernon. “Life is a mirror, man,” he mocked, slowing down his speech and adding Vernon’s characteristic cool-guy drawl. “It, like, reflects . Life is a reflection, man. You know?”

He laughed so hard, he fell over and Vernon rolled his eyes and flipped him off.

“Mingyu,” said Seungcheol. He looked down at the three lines left on the table and asked, “You wanna try?”

The front door opened before Mingyu could answer. Jeonghan walked in, threw his bag in the corner, and joined them in the living room with his usual contended swagger.

“Hey, gents,” he said, his eyes falling to Joshua who was still rolling around the dusty floor. “Did I miss the party?”

“It’s just getting started,” said Seungcheol. He patted the empty couch cushion between Mingyu and himself and wolf-whistled, but Jeonghan was distracted by the goods on the coffee table.

“You bastards,” he said. “You got started without me?”

“Sorry,” said Joshua, making himself sit back up. “You’re right. It’s ladies first.”

Jeonghan flipped him off, too, then knelt beside the coffee table and inhaled the second line of powder. It was so smooth, it seemed like something out of a movie, like something from the scene of an 80s music video. Then Jeonghan stood back up, wiped the excess powder from his nose with a delicate finger, and fell giggling into Seungcheol’s lap.

They had always been close, always been comfortable being physically affectionate. Seungcheol laughed, too, pulling Jeonghan closer to his chest, and Mingyu unconsciously angled his body away from them. Seungcheol noticed this and frowned but Jeonghan didn’t seem bothered.

“Don’t mind him,” said Jeonghan, sitting up straighter so he was straddling Seungcheol’s thigh. “Mingyu is a wonderful young man but he’s…unevolved. He still thinks he can catch homo by close contact, like it’ll rub off on him. Gotta be careful, Cheolie. Those gay cooties will get you every time.”

Everyone laughed, even Jihoon, and Mingyu felt stupid. He slumped down where he sat but Seungcheol didn’t let him get too far, reaching over Jeonghan and slapping Mingyu’s thigh.

“Take a hit, big guy,” he said. “This party is for you, too. You graduated! You’ve earned the right to have a little fun.”

Still feeling stupid, and still trusting Seungcheol with every fiber of his being, Mingyu shrugged his broad shoulders and leaned over to the coffee table. He was entitled to a little fun, wasn’t he? After all he’d been through, why not party with his friends?

He hesitated, suddenly feeling every bit as inexperienced as he was, then he lowered his head and fumbled his way through snorting the third line of white powder. He’d never inhaled anything before and it burned his nose. He winced and coughed, causing Joshua to laugh again, but then sat up straight, shook his head and re-centered himself.

“Atta boy,” Seungcheol said, smirking proudly.

“Welcome to the club,” Vernon said, grabbing a Snapple bottle off the coffee table and raising it like a champagne glass. “Hear, hear!”

“One of us, one of us!” Joshua chanted, a reference to some obscure movie that only he and Jihoon had ever seen. “Gooble gobble, gooble gobble!”

Mingyu fell back against the couch, not sure what would come next. His heart drummed against his chest, expectant, and his hands clenched into fists over his knees. It wasn’t how he’d expected to spend his night but at least he was among friends. At least he was safe, safe to experiment and safe to play.

“Hey, speaking of drugs,” Jeonghan said, still draped across Seungcheol like a sweater, “where’s the baby?”

“Dino’s coming,” Seungcheol said. “He said to start without him.”

Jihoon had taken a few hits from Vernon and then gave him back the blunt, watching Seungcheol and Jeonghan with careful eyes.

“Probably off getting into trouble,” Vernon said, puffing away. “You know how kids are.”

“No one knows it as well as you,” Joshua said. He was still laying on the floor. Mingyu was pretty sure the drugs hadn’t hit him yet and Joshua was just being an for the sake of being an . “You’re repeating senior year for, what, Vernon, the fourth time?”

“You’ve got a real mouth on you tonight,” Seungcheol said wryly. “Why don’t you go put some food in there instead. I think we like you better with your mouth full.”

Joshua closed his eyes and smiled.

“Now you sound like all of Jeonghan’s ex-boyfriends.”

“Hey!” Seungcheol roared but Jihoon intervened.

“Ignore him,” he said. “Let him be a . He’ll tire himself out.”

“Yeah, you tell him,” Joshua continued smugly, crossing his arms over his chest. “Blessed are the peacekeepers for they shall be called the children of God.”

Mingyu had started to sweat. It was a combination of his fear of the unknown (he’d never done real drugs before – what was going to happen to him?) and the sudden tension that filled the room. Joshua could be an , but why was he being one now? This was his party, too.

“Life is like a mirror,” Vernon said, already back inside Vernon Land where he belonged. “You were being a douche-lord but you made a good point, Joshy. Life is like a mirror.”

Without opening his eyes, Josh gave him the double-guns.

“Anything for you, babe.”

It was another few minutes before Mingyu started to feel anything. He’d gotten lost in his thoughts, lulled into serenity by the dull buzz of the surrounding chatter. Life was like a mirror. Why did Josh think that was stupid? Vernon understood it. Did Vernon see it, too? The way that they all reflected off of each other? Life was like that, reflective, but also just as fragile. It could break, it could shatter.

“Seven years of bad luck,” Mingyu mumbled. His mouth felt dry. He looked around the room. Jeonghan was off of Seungcheol’s lap and had made himself a plate of food. He was standing across from the TV, eating. His lips were moving, saying something but Mingyu wasn’t listening. He felt warm, content, slightly drunk despite not having a drop to drink since that whole incident with Yoona.

His ears were ringing slightly and his body felt heavy. He felt tired, but not in a bad way. Not fatigued, but drowsy. Not exhausted but… cozy. He also wanted more food but didn’t trust his legs to support him. So he stayed where he was and kept looking around.

How much time had passed while he was daydreaming?

Joshua was on the love seat now, right next to Vernon, his feet on the coffee table. Jihoon was in the kitchen, sitting near the window. Seungcheol was still on the couch but preoccupied with his phone.

“What’d you say, kid?” Seungcheol asked absentmindedly. “You okay? You need something?”

“Seven years of bad luck,” Mingyu repeated, trying to annunciate. “If you break a mirror, you get seven years of bad luck. Life’s like a mirror, but when do you get those seven years of bad luck?”

Vernon laughed out loud and clapped his hands together, looking genuinely delighted.

“Spoken like a true stoner,” he giggled. “Another one bites the dust. Thanks, Seungcheol. I was getting lonely here. All this time, I thought Mingyu was a choir boy.”

“A choir boy who smokes like a chimney and beats up losers like me and Jihoon,” Joshua laughed.

“God, just leave him be,” Jihoon yelled from across the room. He was eating a cookie. Seungcheol must’ve brought dessert, too. Joshua turned to look at Jihoon but Mingyu turned to look at the TV. Someone had changed the channel and now cartoons were on. “Leave him alone, Josh. Seriously.”

“Fine, fine,” he said with a sigh, sounding bored. There was no challenge in it for him so he didn’t care. “I’ll leave your bully alone. Another alpha getting more than he deserves.”

“You’re such a , Josh,” Vernon giggled. “Mingyu is good to you.”

“He’s not good to people like me,” Joshua retorted.

Mingyu opened his mouth to defend himself but found that he couldn’t. He couldn’t find the words or the strength to speak them. Joshua was right, anyway. Mingyu was a bully. He didn’t smoke that much anymore, though, and that was what he wanted to correct. But he didn’t. He just looked at the TV and watched a cartoon wallaby shout at his friend, the turtle. He laughed because it was a ridiculous concept, unbothered by the fight about him happening all around him.

“Just leave him alone,” Jihoon said. “He’s a good guy with a bad reputation.”

“He wasn’t good to Hoseok when he shoved him in the locker, and he wasn’t good to Soonyoung when he pulled his pants down in front of everybody and he wasn’t good to Kyungsoo when he threw him across the locker room. I must’ve missed all the other good deeds in Mingyu’s past.”

“I’m sorry for all that,” Mingyu said, sighing heavily. “I was an but that’s not me.”

Seungcheol turned to him slowly, then examined him.

“We know,” Seungcheol said, giving him a light punch in the shoulder. “It’s okay.”

“My dad’s an , too,” Mingyu tried to explain but Joshua cut him off.

“Whose isn’t? Get over yourself, Mingyu. Grow up. Make your own choices.”

“I know,” Mingyu said. He could feel his heartbeat throughout his whole body. The hazy sleepiness was beginning to subside, his arms and legs feeling a little lighter, but everything still seemed to be happening a beat slower than it should. “I know that.”

Joshua smiled, a cruel, humorless smile, and said, “Good. Self-realization is so important.”

Mingyu let his head fall back to the cushion behind him. He couldn’t tell if he liked this or not. He certainly didn’t care for the feeling that he wasn’t in control of his own body. He was half-hoping that that sensation would pass and give way to something more pleasant. Euphoric was a word that Dino threw around a lot and Mingyu had to believe there was some truth to that. Dino was the expert, after all. It wasn’t that he felt entirely unpleasant so far, but that he’d been hoping for something more outright enjoyable.

Wasn’t the point of drugs to feel good?

He let his eyes land squarely on the television and then unfocus, just barely letting himself be consumed by the colorful cartoons that flashed and danced behind the glass. He laughed at the slapstick element of it, suddenly finding unexpected common ground with Vernon who sometimes smoked himself into a stupor and then spent a few hours watching Minecraft videos on his phone, completely entranced.

Some time passed. Mingyu’s growling stomach reminded him that he was conscious and he looked to the kitchen table to see if any food was left.

“Can I have more chicken?” he asked.

Seungcheol, who was still beside him, nodded.

“Go for it,” he said. “I’d prefer you eat it all instead of it going to waste.”

Confident that his legs were now strong enough to carry him, Mingyu stood. All the blood rushed to his head, enough to make him giggle but not enough to send him back on his . He felt pleasantly buzzed, like his heavy haze had faded into a much more familiar and much more agreeable type of high.

He made his way across the living room, stepping over Josh who was sprawled out on his stomach playing poker on his phone, and his strides felt airy. A few pieces of chicken remained in the bucket and, not in the mood to be bogged down by polite social conventions, Mingyu picked the whole thing up and hugged it protectively to his chest.

“I love chicken,” he said, mostly to himself as he reached for a drumstick. Then he looked to Seungcheol and said, “Thanks for dinner.”

“Don’t mention it,” Seungcheol said, not looking up from his phone. When no response from Mingyu came, Seungcheol glanced up and gave him somewhat of a forced smile. “Really, don’t worry about it. I get it such a discount, it’s practically free.”

“You’re a good leader,” Mingyu said, his mouth full of extra-crispy chicken skin. He moved closer to his friends, leaning against the wall so that he could still see the TV. “You take good care of us.”

From the couch, still sitting pretty beside a clingy Vernon, Jihoon snorted.

“Oh no,” he said. “Mingyu’s a lovey-dovey drunk.”

“No, I’m not,” Mingyu protested, chewing slowly. “I just appreciate Seungcheol for looking out for us. He feeds us. He gives us gifts.” He dropped a hand down to pat the lighter still in his pocket. Okay, maybe he was a lovey-dovey drunk. “I appreciate what he does. That’s all.”

From the floor, Joshua laughed. He was propped up on his elbows, his dark eyes fixed on the cards on-screen. Mingyu would’ve bet anything that Joshua was gambling with real money rather than just a free-to-play video poker app. He definitely needed to be risking thousands of actual dollars, otherwise, it wouldn’t have held his interest.

“Oh, captain, my captain,” he declared. He looked up at Seungcheol, a dark, trouble-making glint in his eye, and said, “Mingyu loves you. I think you might be his hero, Seungcheol.”

“Eat me,” said Seungcheol, not bothering to take Joshua’s bait.

“It’s not just me,” Mingyu went on, not registering what Joshua was trying to do. Perhaps he was too high, or just too stupid, to avoid walking right into a trap. “Seungcheol is good to all of us. Dino, Vernon, Jihoon, Jeonghan.” Mingyu’s forehead creased and he glanced around the room. “Hey, where’d Jeonghan go?”

Joshua laughed again, high-pitched and cold, the humorless giggle of a budding super villain. It was eerie the way it echoed off the walls of Aunt Helen’s house, a joyless harbinger, a sign of things to come, something that felt strangely like the unnatural calm before a storm.

“Oh yeah!” said Josh, grinning. “He really takes care of Jeonghan. Right, Seungcheol? He’s something of a special case for you, right? You pay extra-special attention to him.”

“Shut the up, Josh,” Seungcheol growled. His eyes narrowed, his face twisting into a mean scowl that Mingyu had never seen before. Seungcheol rarely raised his voice, the type of guy who almost never got angry. But for whatever reason, Joshua had gotten under his skin and in an instant, Mingyu saw Dr. Jekyll give way to Mr. Hyde. “I mean it. Watch your ing mouth.”

Still smiling like the Joker, Joshua pushed himself up and sat with his legs crisscrossed and back straight. There was a challenge in his eyes, a dare. He’d gotten Seungcheol to bite and now he just needed to reel him in. This development had caught the attention of Jihoon who looked nervously across the room, his eyes crossing behind Vernon’s back.

“Guys, come on,” he said meekly. “Let’s not do this.”

“No, Jihoon, this is important,” Joshua said, faking the arrogance in his voice. He was putting on a show the way he tended to do sometimes, so bored inside his own life that he needed to shake things up just to keep himself from falling asleep. “Mingyu needs to know the truth about Seungcheol. Hero worship is dangerous. He’s old enough now to hear the facts and make his own decisions. He’s a big, tough man. Aren’t you, Mingyu?”

Unable to discern the insult from the rest of Joshua’s spiel, Mingyu shook his head, dazed, and said, “Seungcheol is a good guy. What do you mean? What truth? He helps us.”

“Does he?” Joshua rocked his head from side to side, from one shoulder to the other, pretending to think. “Perhaps he does. He buys us dinner, buys us drugs, buys us beer. But it’s not free, is it, Seungcheolie?”

“Ugh,” Vernon groaned dramatically, running both hands through his unruly hair. “Why do you have to be like this, Josh?”

“What do you mean it’s not free?” His face was pulled tight, an uncomfortable grimace. He felt dumber than usual, unable to keep up with what his friends were saying. He wanted to blame the drugs but in reality, wasn’t he just an idiot? Wasn’t that what Joshua always implied? Wasn’t that was his father always told him?

“Seungcheol is happy to help as long as he gets his wet,” Joshua went on, smiling proudly. His tone was dripping with venom, something acidic that Mingyu thought would somehow actualize and burn holes in the floor of Aunt Helen’s home as it spilled from Josh’s mouth. “How old was Jeonghan when you met him? Fifteen? And how old were you? Twenty? Twenty-one?” He scoffed and looked Seungcheol up and down, sneering in disgust. “Is that even legal?”

Mingyu felt like he’d been punched and he physically recoiled, an instinct that he’d developed from years of being used as a heavy bag.

“Wait, what? You and Jeonghan?” He looked to Seungcheol who was staring daggers at Joshua, his nails digging into the fibers of Aunt Helen’s couch, threatening to tear the upholstery. “When did… Why would you…” He blinked a few times, suddenly feeling dizzy. He was still holding the bucket of chicken and the smell of grease wafted up into his nostrils and sent a lead brick to his gut. “Jeonghan sleeps with older guys because of what happened to him as a kid. You told me that.”

“And how do you think he knows that?” Joshua asked petulantly, sitting up straighter and failing to hide the look of bliss in his eyes. He lived for this. “Don’t you ever notice, Mingyu, that when Jeonghan is getting mixed up in some , Seungcheol is right there with him? Remember Mr. Enders?”

“The gym teacher?”

“You know, of course, that Jeonghan slept with him a few months ago, right? And who do you think helped arrange that? Who do you think drove him to the hotel and made sure no one saw Mr. Enders there?” Joshua laughed like a madman when Mingyu stared blankly in response.

“Why would you do that?” Mingyu asked dumbly. He asked dumbly because he was dumb. A big, dumb jock, too high for his own good and holding a bucket of chicken.

Joshua shrugged flagrantly. Seungcheol was still avoiding Mingyu’s gaze.

“My theory,” Josh said flippantly, “is that he likes to watch.”

Seungcheol exploded off the couch, both fists cocked, but Vernon was off the loveseat fast enough to interfere and force him back down.

“You son of a !” he roared. “You watch your ing mouth!”

“Okay!” Jihoon said, jumping up so that he could offer his assistance in some way. “Let’s all cool off. We’re all friends here.”

“He’s not my friend,” Joshua said, shrugging. It was so simple, so cold, delivered with the same apathy of his usual regurgitated statistics and fun facts. That in itself hit Mingyu like a right hook to the jaw, hurting him more than it hurt Seungcheol. What did he mean they weren’t friends? They were all friends. They were a family. Weren’t they?

“You really need to relax,” Vernon said. He had one hand on Seungcheol’s chest, keeping him seated, and the other pointing fiercely at Joshua. “You’re not in any position to be talking this much .”

Joshua made a noise halfway between a laugh and a scoff, the sound of pure, unadulterated amusement.

“Oh, really?”

“Yes, really,” Vernon bit back. It was the most backbone Mingyu had ever seen Vernon show and he wondered if his loyalty to Seungcheol ran deeper than it seemed. “You ain’t perfect either, or have you forgotten all about what almost happened in May?”

Joshua’s smile widened into something beyond joy. He was loving this. He’d set it all into motion and he was finally receiving the reaction he’d been hoping for. He was the kid in class who watched others build tall towers with blocks just to come by and knock them down. He relished in the madness that followed, the chaos and the destruction.

“Yeah, Columbine,” Seungcheol muttered. “Why don’t you tell Mingyu about your little Trench Coat Mafia plan, huh? The one that Jihoon stopped?”

Mingyu snapped to look at Jihoon. He looked even smaller than usual, eyes on the floor, cheeks flushed. His head was still spinning, reeling with everything Joshua had forced upon him. Jeonghan and Seungcheol? Really? He felt something in the back of his mind, something thin and fragile, beginning to crack.

“Josh,” Mingyu said. “What did you do?”

Joshua held open his arms, gesturing to Seungcheol.

“By all means, leader-nim, please spin a story for young Mingyu. Tell him the tale of the big, bad wolf and how Prince Jihoon saved the day.”

“Go yourself, Josh,” Vernon muttered, rolling his eyes.

Seungcheol only hesitated for a second, his eyes finally risking a glance in Mingyu’s direction.

“Back in May, Joshua left his bedroom door unlocked. Jihoon thought he was here. He wasn’t. He knocked and opened the door and what should he find but dozens of papers, dozens of plans on how Josh here was going to shoot up the high school just in time for graduation. He had lists of people he was going to kill and detailed exactly how he was going to do it.”

The room fell silent.

Joshua’s smile was reserved.

“What?” he said quietly. “A boy can’t fantasize?”

“You had three guns and the makings of a bomb in your footlocker,” Jihoon blurted miserably. Even with his head down, Mingyu could tell he was on the verge of tears. His fists were clenched at his sides and he was cowering like he was expecting to be hit. “You were really going to do it. You were really going to come to school and kill a bunch of people. You were going to kill some of our friends.”

“They aren’t my friends,” Joshua said, flabbergasted. “And they’re not yours either, Jihoon. Grow up. They terrorized us for years. Why so much sympathy for the devil?”

“I knew I should’ve called the cops on your crazy a long time ago,” Seungcheol said. He moved to stand up again but Vernon pushed him back down.

“I should’ve called them on you, too,” Josh said deliriously. Somewhat sluggishly, he raised his right hand to his ear, sticking out his pinkie and thumb to make a phone. “Hello? Officers? I’ve got a fifteen-year-old friend who s with older guys. Teachers, truck-drivers, whoever you’ve got. Do I know of any specifics? Well, I know a twenty-one-year-old who s him in return for booze and rides to work.” Joshua threw his head back and snorted with laughter, only laughing harder when he saw the look on Mingyu’s face. “Oh, Mingyu. Get real. Didn’t you ever wonder why Seungcheol doesn’t hang out with anyone his own age?”

From the couch, Seungcheol growled again, an angry, hungry predator that needed to be restrained. But Vernon held strong.

He felt it again, something cracking. It had started off small, a nameless, faceless itch at the base of his brainstem, but it was growing rapidly, splintering and turning into clusters of webbed fractures. But what was it that was breaking? His grip on reality? His fleeting grasp on sobriety? His perception of his friends? His deep-seeded loyalty? Or was it that mirror, the one he held up to keep himself safe. He saw pieces of himself reflected in all of his friends, after all. If Seungcheol had been preying on Jeonghan all this time, if Joshua was truly capable of such violence, what did that mean for him? Who were these people? And, more importantly, who was he?

The front door opened and Jeonghan returned. Mingyu didn’t bother asking where he had been, deciding almost immediately that he didn’t particularly need to know.

Jeonghan, always a bit faster-to-the-punch than Mingyu, picked up on the tension right away. Mingyu figured it was tangible, like stepping out of an air-conditioned room and out into the thick fog of mid-summer humidity.

“Oh boy,” said Jeonghan. “What’d I miss?” He scanned the room, looking at each face individually, but stopped on Seungcheol. “You okay?”

Joshua giggled and said, “The queen is back to comfort her king.”

Jeonghan’s eyes narrowed. He looked annoyed but not especially hurt as he said, “Go yourself, Joshua.” He sat on the arm of the couch, right next to Seungcheol, and Vernon lowered his hand, apparently confident that Jeonghan’s presence alone would be enough to quell the murderous rage still burning in Seungcheol’s eyes.

Vernon took a step back and Mingyu took a much closer look at Seungcheol and Jeonghan. Their body language seemed to broadcast something that Mingyu had just simply never realized. Jeonghan put his hand on Seungcheol’s back, something that any one of them might’ve done to calm a friend down, but his touch lingered. He rubbed circles with his palm and Mingyu watched as Seungcheol relaxed into his touch, his jaw finally beginning to unclench.

So it was true, then.

The door opened again. In walked Dino with a smile on his face, a young man completely oblivious to the warzone into which he’d just stumbled headfirst. He had his backpack slung over his shoulder and his lime green t-shirt boasted a lizard wearing sunglasses.

“Sorry I’m late,” he announced boisterously. “What did I miss?” He seemed to take it in all at once – the way Jeonghan was comforting an obviously irate Seungcheol, the way Vernon and Jihoon stood in the middle, awaiting a physical altercation that had yet to come, Joshua on the floor looking like a kid who’d just taken cookies from the cookie jar, the drugs on the table and Mingyu standing against the wall, holding a bucket of chicken. “Wow,” he said, smirking. “I guess I missed a lot. You guys sure know how to party.”

“The gentlemen were just clearing the air,” Jihoon said diplomatically, putting on a brave face for the youngest member of the group. He stood up straighter, the tears threatening to spill from his eyes moments before suddenly retreating back into their ducts. “You know how guys are. Things are just getting a little tense.”

Dino nodded, a wrinkle appearing in the center of his forehead.